+

Fr. Uwe Michael Lang of the Oratory writes:

(Roger) Scruton is aware of the need to recover the metaphysical foundations of beauty, which were eroded in the eighteenth century, when “aesthetics” became a separate philosophical discipline, but in the end, he cannot do so and must limit himself to the judgement of taste.22 Certainly, an education of taste would go a long way, but, in the end, de gustibus non est disputandum. In other words, a well-honed aesthetic instinct cannot provide foundations stable enough or strong enough to rebuild the metaphysical underpinnings of the arts today.

Elements of a theological response to this question are found in a renewed appreciation of the Christian tradition. In a well-known passage from his novel The Idiot (1869), the same Dostoevsky has his Christ-like hero, Prince Myshkin, say,

“I believe the world will be saved by beauty.”

Not any beauty is meant here, but the redemptive beauty of Christ.

In a profound reflection on this subject, written in 2002 for the annual Communion and Liberation meeting in Rimini, the then-Cardinal Ratzinger comments on Psalm 45(44), which praises the king at the occasion of his wedding and exalts his bride. In the exegetical tradition of the Church, this lyrical psalm has been read as a representation of Christ’s spousal relationship with the Church and the description of the bridegroom as “the fairest of the sons of men” as Christ himself. Where the psalm declares that “grace is poured upon [his] lips”, this is taken to refer to the beauty of his words, the glory of his proclamation.

Ratzinger notes that it is “not merely the external beauty of the Redeemer’s appearance that is praised: rather, the beauty of truth appears in him, the beauty of God himself, who powerfully draws us and inflicts on us the wound of Love”.23

|

| Cimabue / Arezzo |

This beauty attracts us and makes us join the procession of Christ’s Mystical Bride, which is the Church, going out to meet the Bridegroom. Presenting us with a stark contrast, the Church applies to the same Christ, who is praised as the “fairest of men”, the words of Isaiah 53:2: “He had no form or comeliness that we should look at him, and no beauty that we should desire him.” This is done in remembrance of his Passion and shows the “paradoxical beauty” of Christ, which implies a contrast but not a contradiction.

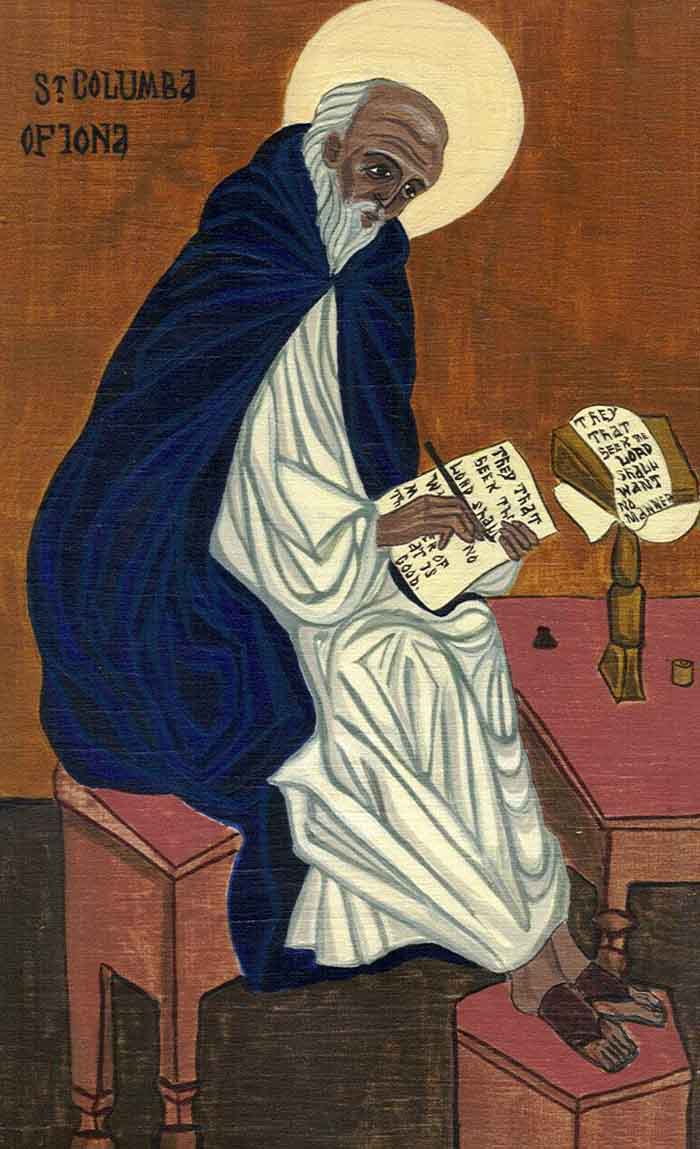

As Ratzinger observes, we come to know that “the beauty of truth also involves wounds, pain, and even the obscure mystery of death and that this can only be found in accepting pain, not in ignoring it.”24 The totality of Christ’s beauty is revealed to us when we contemplate the disfigured image of the crucified Savior, which shows us his “love to the end” (cf. Jn 13:1). This is the beauty that will save the world, the redemptive beauty of Christ, crucified and glorified. It shines forth with particular splendor in the saints but is also reflected in the works of art the faith has generated. The masterpieces of sacred art have the power to lift our hearts to higher things and lead us beyond ourselves to an encounter with God, who is Beauty itself.

Lang, Michael (2015-10-05). Signs of the Holy One: Liturgy, Ritual, and Expression of the Sacred (pp. 101-103). Ignatius Press. Kindle Edition.

+